“Irena” is a graphic novel series dramatizing events in the life of Irena Sendlerowa, a Polish social worker who saved 2,500 children from the Nazi-occupied Warsaw ghetto. The story is distinctly moving as a graphic novel, and I want to share a few things I appreciated about Morvan, Evard, Trefouel, and Walter’s articulation of it in the comics medium.

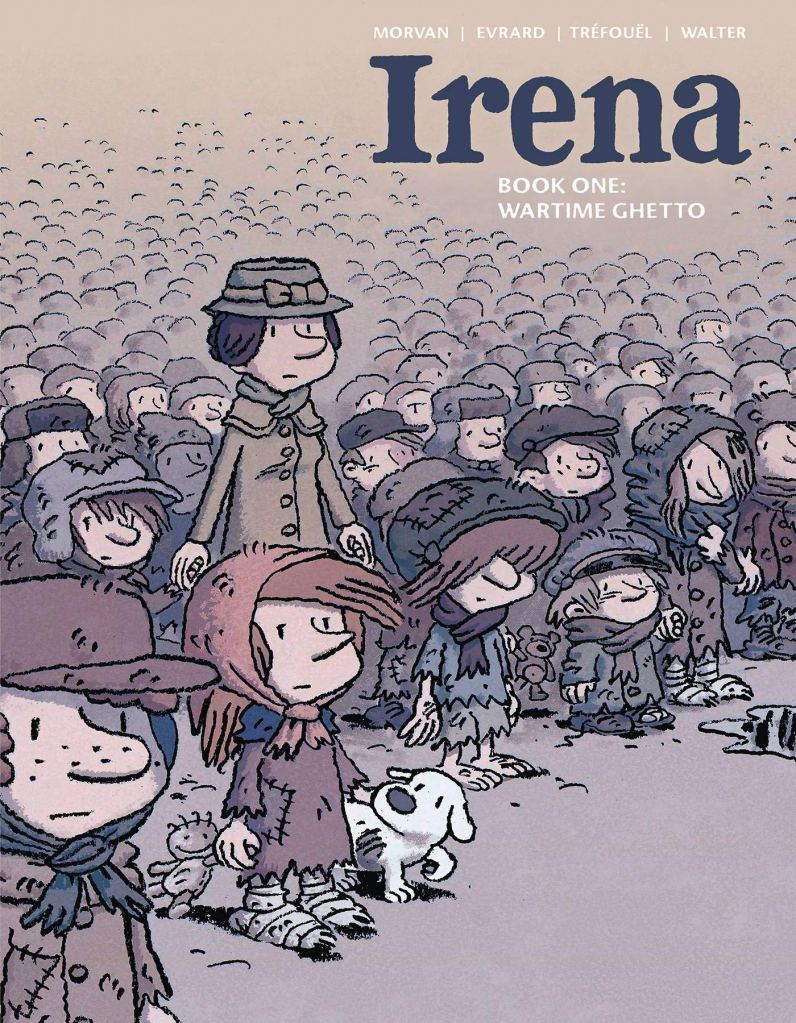

For starters, a subtle element of the cover design: everything is a matte finish except Irena and her dog, who are covered in full gloss. They get special treatment as rescuers, saviors, and heroes among the children, but the exceptionalism is subtle and only perceived by deliberately shifting the image in the light. Otherwise, viewed head-on, they look as drab and sullen as the sea of children with whom they walk across a barren plain.

A two-page spread appearing early in Book One is a feat that no medium besides comics could accomplish. In it, Irena and her coworker drive their supply truck through the Warsaw ghetto. At this point, the Nazi government still permitted the Polish Social Welfare Department to bring in aid provisions for the Jewish residents of the ghetto, albeit meager and inadequate. The truck is shown advancing through the scene three times in the same image: a narrative sequence is present, but the static page invites poring over in any given direction outside of the left-to-right , forward-through-time”reading.” Children excitedly pursue the truck and chat about all the fine things they fantasize will be in the supply truck this time and how much Irena’s care will improve their condition. The children’s fantasies appear as vividly colored panels taking the place of detention walls, crumbling roofs, and building facades. The background scene and a few pop-up close-ups establish the terrible scene in the ghetto. The spread is both simple in the broad strokes of dreary scenery and the sometimes colorful images floating over it and complex in the details populating it. The result is a Where’s Waldo of misery and dreams.

The remaining items I’ll mention aren’t feats that can be accomplished exclusively by comics, but they’re feats performed incredibly well in this one.

The first is a continuation of elements in the “Where’s Waldo” spread. Later in the story, the overlaid, colorful dream plane device is deployed again, when Irena and her accomplices smuggle a girl out of the ghetto and into a new place to stay. Her dreams of royal treatment and triumph against monsters play out in roadside puddles and waxed floor reflections as they move through the streets and into various halls and crypts of Polish institutions. Her mirror-world fantasy has some correspondence, finally, to her reality. Color returns to the prospects of the dark and murky world.

Ghosts appear in this story, sometimes materializing unexpectedly and tragically, and sometimes behaving in ways I didn’t expect. Their white and blue colors are a stark contrast to the dull tones pervading the scenes where death is likely to appear, as when Irena is captured and interrogated by the SS. She refuses to talk, and the guards beat her and throw her back in her cell. She lays bruised and bloodied on a dirty mat when the ghost of her father appears. He had been a selfless helper, a doctor who died of typhus while treating an outbreak in central Poland. Now his blue translucent essence sits beside Irena and pets her hair, “Oh, my little Irena…” he begins. I expected words of sympathy or some recognition of her suffering next. He smiles and expresses an altogether different tenderness instead: “…I’m so proud of you.”

Much has been said about the complex and challenging meanings overlaid onto stories of the Holocaust through cartooning by Art Speigelman in Maus, especially the intentional problematics of giving different animal faces to different nationalities, but the effects of the perhaps simpler choice of rendering a real-world story of mass misery and catastrophe as a cute cartoon with cute-looking human characters (and one dog) are just as striking for me. I’m no more or less moved by this story per se; no less frightened when the characters are in danger or taking new risks, no less devastated when tragedy strikes, no less joyed when Irena’s network delivers another child from deprivation and extermination. But the visual”cuteness” augments the tenor of the whole affair, in both the miserable and the transcendent passages. “Cuteness” is a designation for people or things which one loves and wants to care for. Cute things are also regarded as harmless, and the cute visual style does take the edge of for sensitive or younger readers–though not as much as you might assume. The aesthetic insinuation of “Irena”‘s cuteness, for me, is that anything and everything in the world can be observed with an edge of ligthness and love. This books loves humanity and courage; it loves and praises a sharp-edged woman who cared for and rescued many from–and in so doing fought against–a socio-political order that devastated the earth and which this book, it its every stroke of cuteness, explicitly and implicitly damns to hell.